Michigan's Best Songs: The story behind college football's greatest fight song

A deep dive into 'The Victors,' from its superfan creator origin story to the controversy surrounding its familiar melody.

As far as one-hit wonders go, you could do a lot worse than Louis Elbel, a 21-year-old University of Michigan student whose passion for his school’s football team inspired a song infinitely more popular today than when he penned it more than 125 years ago.

If you’re from Michigan or have any knowledge of college football, there’s a good chance you already know the song I’m talking about. I’m sure you either love it loathe it — depending on your fan allegiance — but there’s a good chance you know all the words to it, either way.

That’s why when my wife sent me a video last week of The Victors being played by a band inside the Grand Hotel on Mackinac Island as women of all ages participating in a religious retreat clapped to its cadence, I knew I needed to go long on the University of Michigan’s fight song and how it became recognized as one of the best in all of sports.

I had been searching for the perfect song to debut for a series on this blog that aims to tell the story of songs that define our state. Think Bob Seger’s Roll Me Away, The Accidentals’ Michigan and Again or Da Yoopers’ Second Week of Deer Camp, to name a few.

Following the unexpected euphoria of Michigan’s recent win over Michigan State, I found myself inspired to combine a couple of my loves — music and college football — for a very biased deep dive into the history of this iconic fight song, aided by a research trip to the thoroughly awesome Bentley Historical Library on the University of Michigan’s North Campus.

Ever the marketing genius, I’ve decided to label The Victors as the first in this series of MICHIGAN’S BEST SONGS! We can work on the title later — but for now, here’s how The Victors came to be.

Champions of the West

On a freezing cold Thanksgiving Day in 1898, Louis Elbel was one of 600 students who traveled by train from Ann Arbor to Chicago to see if the undefeated Wolverines could exact revenge on a team that had its number the past two seasons.

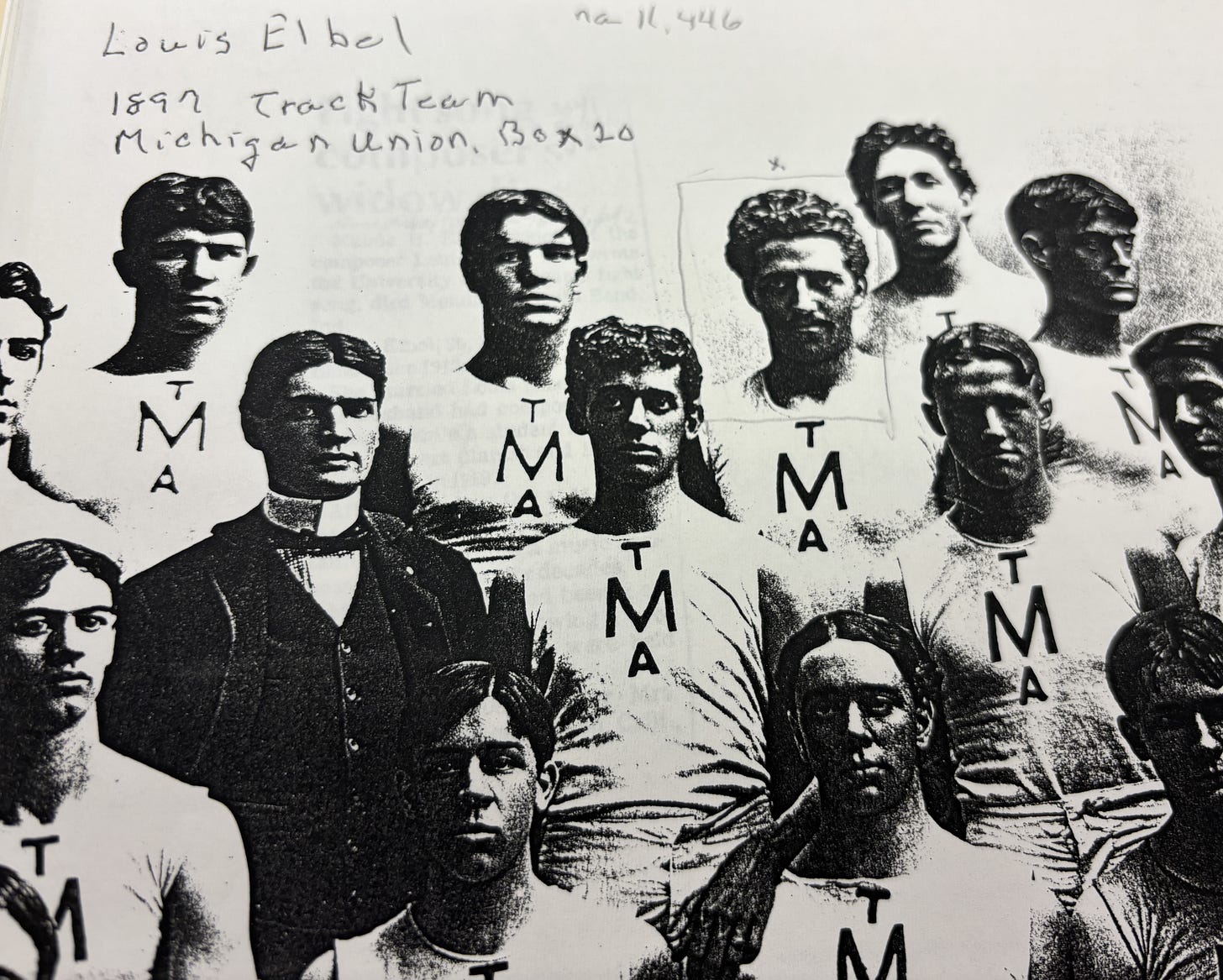

Then in his third year studying music at UM, Elbel was a gifted piano player from an early age. Despite being just a shade over 5 feet tall, he also was a talented athlete and a sprinter on Michigan men’s track team.

Before Michigan went on a run of winning national titles and padding its resume as a college football Blue Blood in the early 20th century under legendary coach Fielding H. Yost, its biggest rival wasn’t (the, lowercase) Ohio State University or its in-state rival Michigan State, but a budding institution a few hours to the west — the University of Chicago.

In a 1984 article published in Sports Illustrated, author Ivan Kaye noted the University of Chicago had quickly risen to academic and athletic prominence just seven years after it was established behind the millions invested by John D. Rockefeller.

Chicago had lured away top professors from established universities, including the University of Michigan’s John Dewey, who Kaye described as later going on to become “the colossus of American education.” Its football team, on the other hand, had set the standard for the recently-established Western Conference that would later become the Big Ten - a much more apt title for a conference that now has something like 38 teams.

Elbel traveled to Chicago with revenge on his mind, recalling in an article he penned for The Michigan Alumnus that following losses to Chicago in 1896 and 1897, “There was not a sadder Michigan man there when we lost to Chicago in both games.”

The game Elbel and 12,000 fans at Marshall Field witnessed in 1898 was an instant classic, even if the history surrounding how it unfolded is a little fuzzy. What’s not disputed is that an epic, 65-yard fourth quarter touchdown run by Michigan’s Chuck Widman helped secure a 12-11 victory over the Maroons. Back then, touchdowns were only worth five points and Michigan had blocked one of Chicago’s extra points, which proved to be the difference in the game.

Widman’s TD run was the stuff of legends, author John Kryk wrote in his 2004 book Natural Enemies. Check out this insane passage about how the run unfolded:

On his winning score, Widman was merely trying to buck the line when a group of Chicago tacklers began pushing him backward. But Widman twisted away, broke outside, and sprinted down the sideline, with Chicago right end Ralph Hammil in hot pursuit, just a few feet behind. Two Maroons tacklers had the angle on Widman and tried crowding him out of bounds but couldn’t. Finally, Hammil dived and tripped up Widman just a few yards short of the goal. But back then, ball carriers were not deemed tackled until held down or until they cried out, “Down!” So Widman proceeded to crawl across the goal and touch the ball down for the go-ahead score.

Widman’s proto-Beast Mode run contributed to the pandemonium that would follow as Michigan fans marched through the streets of Chicago celebrating an undefeated 10-0 season. The Chicago Tribune bestowed Michigan’s season with the title of “Championship of the West,” while the headline atop the Michigan Daily the following Monday simply read “Champions of the West.”

While that phrase is now a part of UM vernacular, back then, the win was a pretty big deal:

“It raised Michigan, which otherwise would have finished the season among the ‘also rans’ to the rank of victor,” the Tribune’s article stated.

A song for ‘no ordinary victory’

Following the victory, Kaye described Michigan students doing a “snake dance” up Hyde Park Boulevard and singing themselves hoarse with help from the Michigan Marching Band, which had just established the previous year. Their song of choice was not The Victors, however, but what could be described as Michigan’s first, defacto fight song at the time, A Hot Time in the Old Town.

A traditional marching song for American soldiers, A Hot Time in the Old Town has been used by several universities, including the University of Wisconsin, which continues to play the song after victories.

Prior to the big game against Chicago, a Nov. 23, 1898, souvenir edition of the Michigan Daily printed student-submitted lyrics to some popular marches the band played, including a Michigan-centric version of A Hot Time in the Old Town by UM student A.G. Browne as part of the publication’s sweepstakes surrounding the game. Check out the savage lyrics submitted by Browne forecasting the Michigan W:

Oh there’s going to be a s’prise partie / on Marshall Field today,

So just keep your eyes on Michigan / and watch the way they play.

Though Chicago scored on Pennsy’s team / today she’ll bite the dust,

For we’ve got Bill Caley with us / And there are no flies on us.

While A Hot Time in the Old Town remained a Michigan favorite in the years that followed, Elbel couldn’t shake the feeling that an epic win like the one over Chicago needed something more … victorious.

As he walked the mile and a half from Marshall Field to his sister’s home in Chicago’s Englewood neighborhood for Thanksgiving dinner, the euphoria of the win began to get the wheels spinning in Elbel’s head.

“I guess I was too happy to be bushed,” Elbel later recalled. “… Most of it I walked, and on my way thoughts came to me that our band didn’t have the right celebration song that night. Neither did Michigan. And a thought came to me Michigan should have one.

“It struck me quite suddenly that such an epic should be dignified by something more elevating, for this was no ordinary victory.”

Remembering the famous walk to his sister’s home, Elbel said the idea for The Victors evolved in his head from a walk into a march. A band got to singing a sort of “victory sound,” inspiring the famous refrain of The Victors in his head — not only the music, Elbel noted, but the words “Hail to the Victors Valiant!” and “Hail to the conqu’ring heroes!”

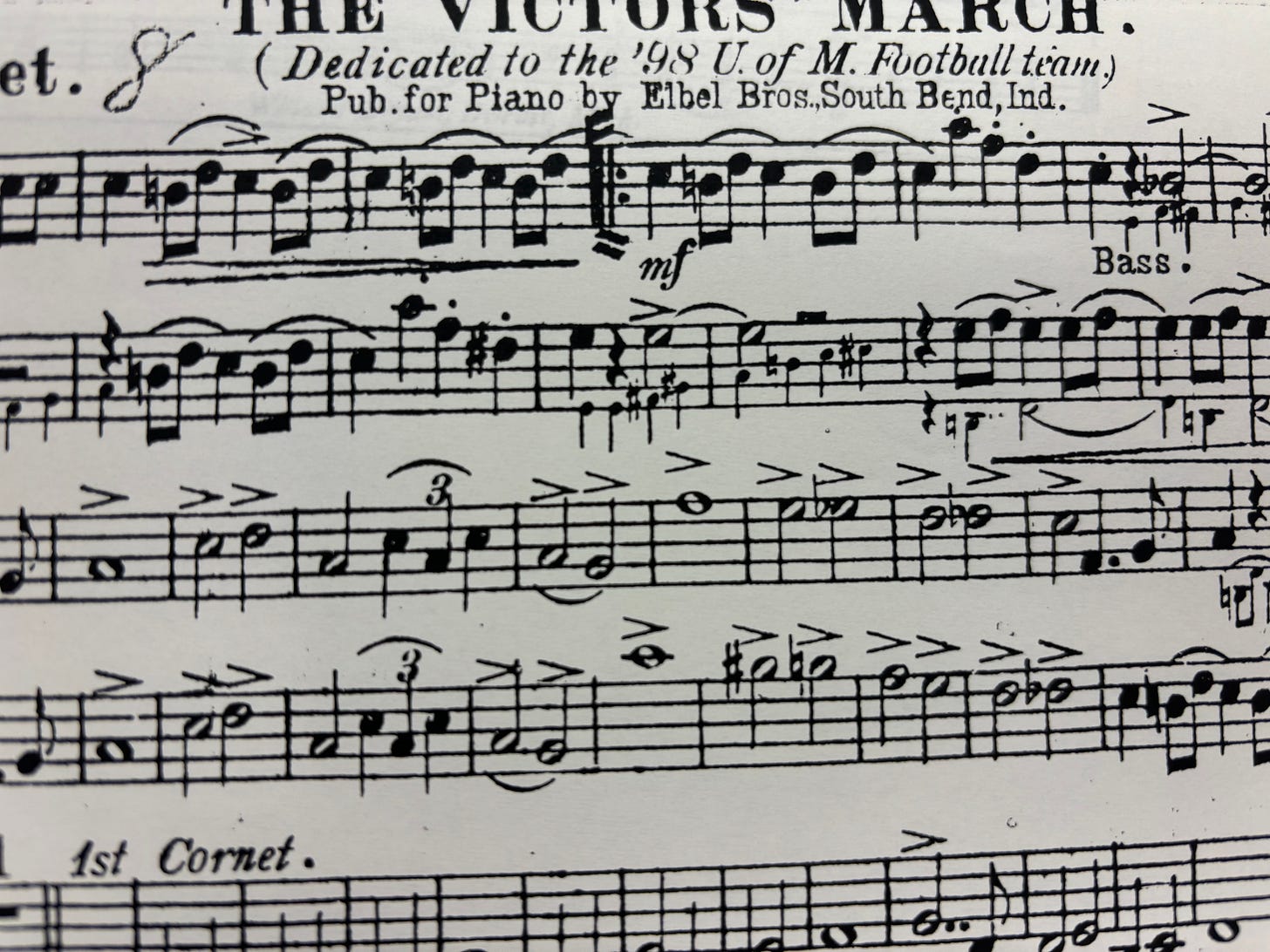

When he arrived at his sister’s home, Elbel had the presence of mind to write down the notes to The Victors during Thanksgiving dinner, because, of course that’s how it happened. Arriving the next day at his family’s home in South Bend, Indiana, he tried it out on piano, finishing the entire refrain. The idea of a “big march” then came to him and he completed the whole work on the train back to Ann Arbor.

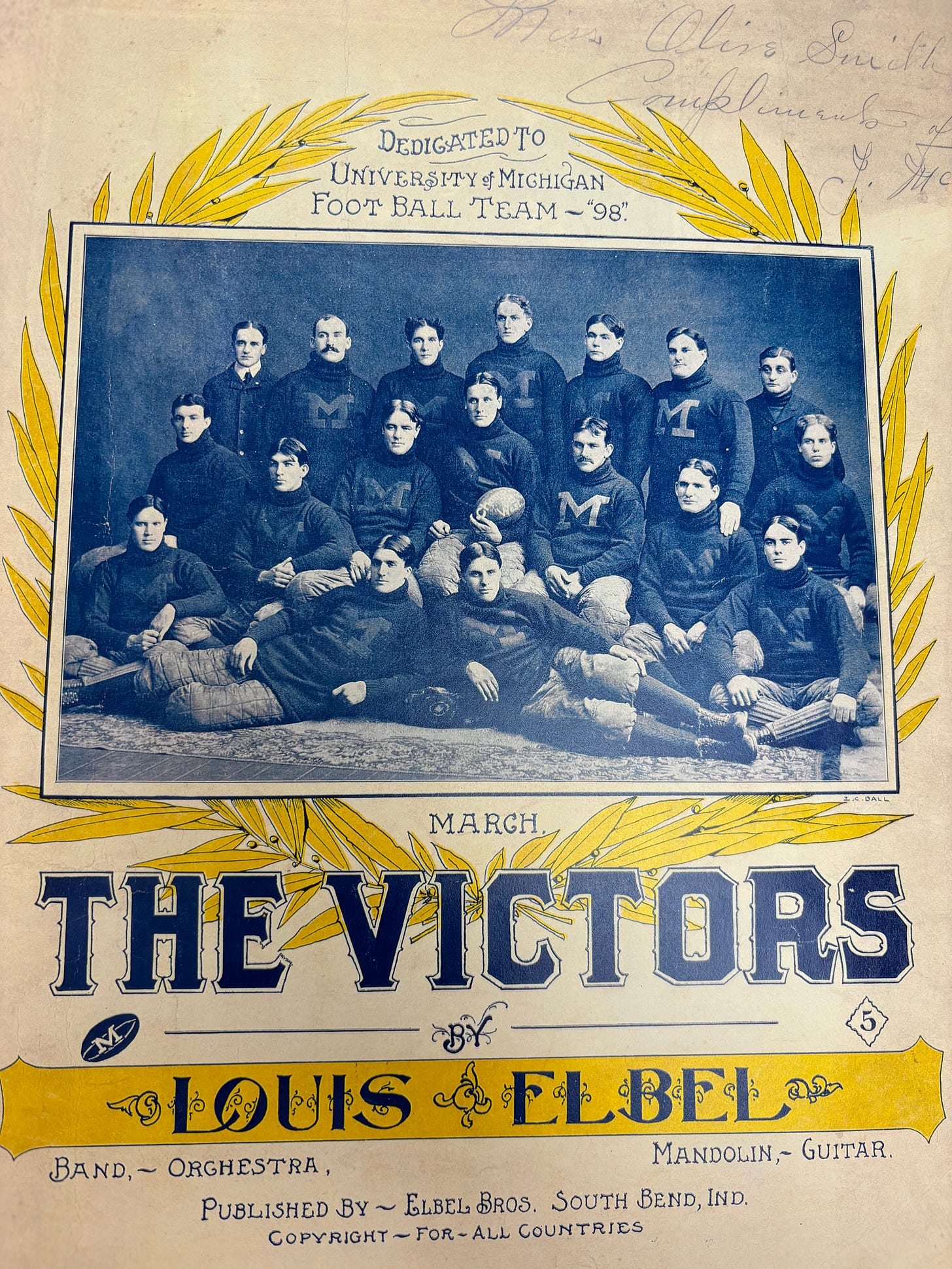

Elbel got in touch with E.R. Scremser, a bandman and arranger in Detroit, who helped make an arrangement for the marching band. The band copy was sent to the printers with 23 sheets provided for that many instruments, Elbel recalled in an alumni magazine retrospective.

“I can’t say that I had any special ideas about this being a big hit,” Elbel said. “But my brother, in the music business, suggested and saw to it that it should be printed. And it was.”

A big debut courtesy of John Philip Sousa

Elbel received his first copy of The Victors march in early April of 1899. Shortly after, The Victors made its public debut during an opening night performance of the University Comedy Club’s production of a show, “A Night Off” on April 5, according to UM Marching band alum and Elbel historian Joseph Dobos.

A Michigan Daily article reviewing the show noted the following:

Elbel’s “latest composition, ‘The Victors March’, was greatly appreciated and an encore was called for after its rendition.”

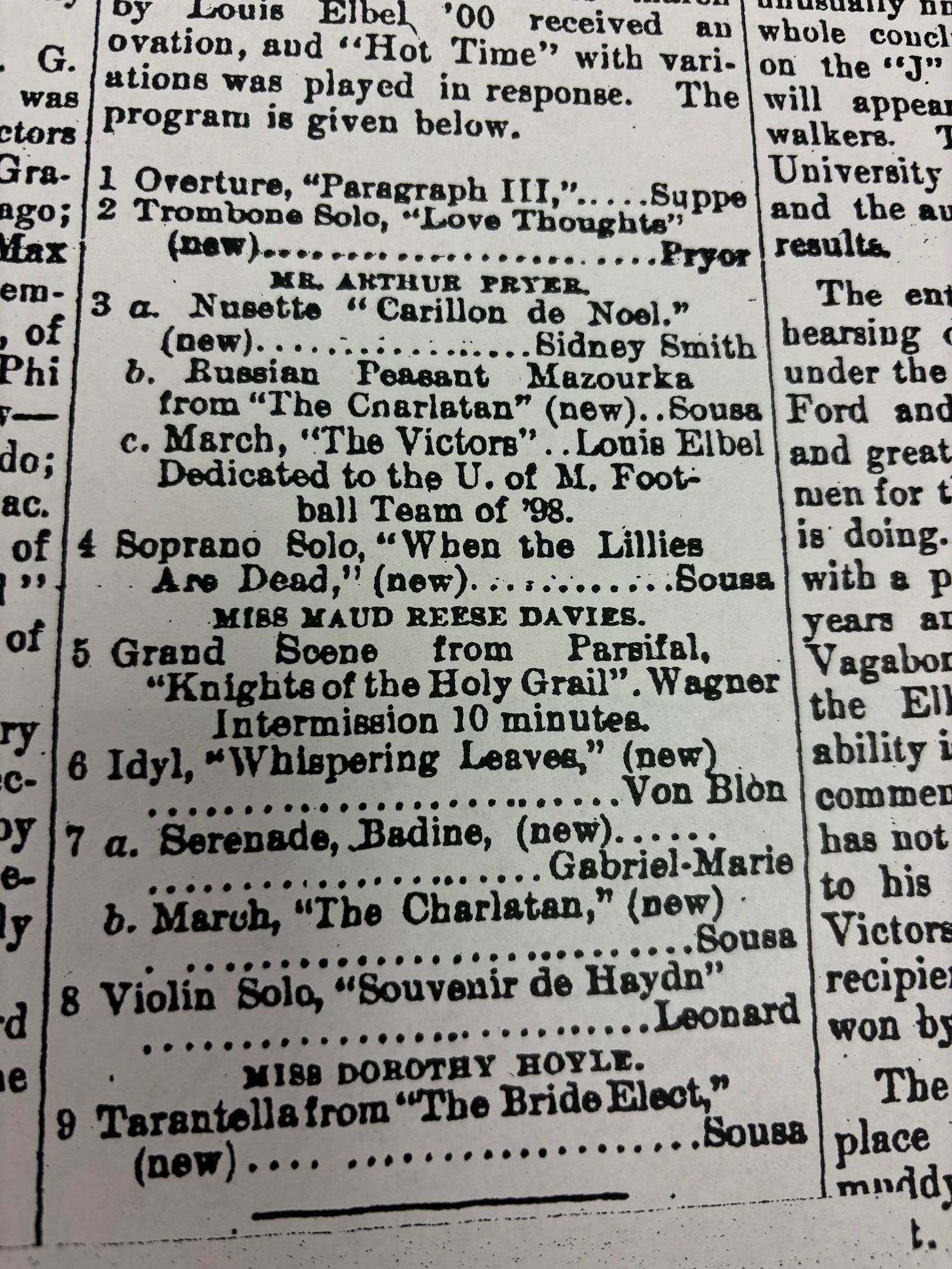

A few days later, Elbel decided to shoot his shot in anticipation of a visit from march composer John Philip Sousa and his legendary band.

One of the nation’s most revered composers at the time, Sousa was to be in Ann Arbor for his band’s performance at University Hall in a fundraiser for the Women’s League. An April 7, 1899 Michigan Daily article previewing the appearance described Sousa being at “the height of his fame” leading up the the performance.

“The entertainment which will be furnished is almost too well known to be commented on,” the article stated. “In its field, Sousa’s band has no equal. It is almost true to say it is an aggregation of soloists.”

Elbel recalled approaching Sousa prior to the concert that evening, presenting him with a new copy of The Victors march and asking him to have his band consider playing it.

Apparently that’s how these things worked in 1899, because the legendary Sousa agreed, immediately organizing for his band to tackle the sheet music.

“He greeted me in a very kindly and courteous manner, and accepted it,” Elbel wrote. “I really didn’t know what he might do with it. But after looking at the solo part, he called his librarian and he placed the parts on the music stands of between 40 and 50 bandmen.”

Elbel was “excited and astounded” Sousa and his band played his march for the first time for a large audience, marking the first time the lyrics to The Victors were sang in public. The April 10, 1899 edition of the Michigan Daily noted the audience responded to the “stirring” music of The Victors by expressing their appreciation in a “vigorous manner” in the form of an ovation from the audience.

Sousa responded with an encore by performing variations of A Hot Time in the Old Town during the performance, later describing Michigan’s new fight song as the “best college march ever written.”

A second author?

If Elbel’s story sounds too good to be true, don’t worry! The Victors’ famed trio — the featured melody of the march — is nearly identical to a march called Spirit of Liberty that was composed a year earlier by George “Rosey” Rosenberg.

Dobos brilliantly documents the timeline of Rosey’s publishing of Spirit of Liberty and how it lines up with Elbel’s, calling into question how Elbel could have been influenced — subliminally or otherwise — by the tune in penning The Victors a year later.

Listen to this clip for yourself of Spirit of Liberty, specifically around the 1:49 mark, and your ears will perk up at the striking similarity between the two melodies.

According to Dobos’ timeline, Rosey submitted his application for the copyright of Spirit of Liberty on April 11, 1898, while two copies of the piano solo were submitted on April 26, 1898. Live performances of the composition can be traced back to June of 1898, all before Elbel was inspired to write The Victors after the Thanksgiving Day 1898 game.

This revelation publicly came to light dating back to 1981 when marching band alumnus George Anderson apparently mentioned it in a very ho-hum fashion during an interview, noted in both Dobos’ timeline and in coverage from The Ann Arbor News/annarbor.com in 2009.

Marching band alumnus Jim Henriksen stoked the controversy decades later in his paper The Authorship of The Victors March, noting that several theories have been floated about how Elbel could have been inspired by Spirit of Liberty’s melody.

“While fascinating to ponder, none of these theories is likely to be proven, and they serve only to mitigate Elbel’s offense by explaining that any influece on “The Victors” was most likely subliminal,” Henriksen wrote.

Dobos defended Elbel in a 2009 story printed in The Ann Arbor News, claiming it never would’ve occurred to him that he was “stealing” the melody from Rosey as a fun-loving college student, adding that Elbel’s is a more tightly-composed “circus march” compared to Rosey’s, which is more of a “two-step.”

“Elbel’s use of Rosey’s melody … is an interesting footnote,” Dobos said in the article.

Despite the striking similarity, there is no question The Victors as a whole is its own thing, even if it is one of many examples in music history of borrowing from and augmenting something that resonates with you. Its introduction, three separate strains, interlude and lyrics all have their own unique characteristics — a fact all historians who have weighed in on the Elbel/Rosey issue agree on.

Adding to the mystery surrounding The Victors in its early years are the signs that it wasn’t used as the school’s fight song in the years that followed Elbel’s debuting of the tune.

Dobos notes coverage of a UM Glee Club concert on May, 24, 1904 from the Michigan Daily described Elbel as having created a special arrangement of “The Victors” for the Banjo and Mandolin Clubs, with the newpaper reporting “the piece has been ordered by the band and will be played from now on at the Saturday games while the football men are marching on the field.”

The timeline also goes on to note Oct. 26, 1905, is the first date, on record, of the UM Marching Band playing of “The Victors” at a train depot as part of a rally to send off the football team for its game against Wisconsin.

The wonderful fan site MGoBlog takes it a step further in The Victors lore, claiming that there have been THREE fight songs throughout the history of Michigan football, with popular marching band tune Varsity serving that role from 1912 to 1916.

Considering the fact that Michigan had left the Western Conference during that time period, as MGoBlog notes, it makes sense that the song’s “champions of the West” lyrics would’ve seemed awkward then — just like they sort of still do today.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Radio Amor to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.